Issue 9: Should I become a manager?

I've answered this question for myself and for my mentees many times over. It's a fork in the road we all consider and I'm happy to make that decision easier for you in a small way.

Welcome, designer.

I feel like an ex calling out of the blue. Nothing for 1.5 years and then suddenly I'm in your inbox. 💀

I took a hiatus on this newsletter to focus on balancing work and life better and now that I'm in a way better spot, I'd love to get back to writing. In the time since, I received so many kind words from people on how this has been helpful in their journey, some as recent as this week. I can't thank you enough for reaching out. This revival issue is for you!

Q: Should I become a manager?

I've answered this question for myself and for my mentees many times over. It's a fork in the road we all consider and I'm happy to make that decision easier for you in a small way.

Some context setting: I have supported teams on Instagram and Messenger (in addition to some startup advising that require hands-on management). Prior to that, I spent 5 years as an IC, climbing the seniority ladder until I was eligible for management.

Reasons to manage others

I'm sure you have some inner inkling of why you may or may not enjoy management already but it also helps to know what motivated others to make the switch and see if you agree with any of them.

My incentives:

Larger scope & visibility. I have always been interested in the bigger picture and shaping the overall product. Towards this, I wanted to operate on a higher level much earlier than the IC track usually allows. Even just having 3-4 reports as a new manager immediately affords me visibility across all of their teams and how their work ladders up to the overall vision.

Accountability for soft skills. While soft skills like communication, influence, and mentorship are needed to succeed as an IC, they take up a much more significant role in management. I like to intentionally push myself in these areas and particularly learn to excel in these areas at scale.

Pixel pushing to pixel coaching. While I deeply care about design excellence, I don't necessarily want to own the execution part of it. Instead, I like coaching others and rigorously reviewing work to ensure a high quality bar. This opens up bandwidth for me to lean into other hard skills that I do want to practice, like product strategy and systems thinking.

More predictable hours. Over my years as an IC, I worked late into the night lining up pixels and burnt out because I had a hard time drawing a healthy boundary. While this is something I improved over time, the collaborative nature of management acts as a forcing function for me to call things a day. There's not a lot I can realistically get done while everyone's logged off and it encourages me to optimize my efficiency before 5pm instead of procrastinating.

Just as important, my non-incentives:

Money / Promotion. It’s important to know that management is a lateral move, not a promotion. Certainly you can get promoted at the same time but that’s more to do with your incredible performance than the innate role itself. I'm lucky that my company (and the leading industry) offers a parallel track for senior ICs with equal pay, which dissuades managing solely for advancement.

Authority. While the manager title evokes a certain level of authority, it is not ultimately what motivates people. Even if I was power hungry, attempting to pursue it for this reason will be disappointing once people quit working with me. Instead, I aim to be influential by positioning myself as a resource on the team that others can count on for feedback or direction.

Key differences between senior IC and management

Similarities:

Upleveling others. As mentioned above, mentoring others is still very much a part of both roles. Believing you won't deal with people as a senior IC is in direct conflict with being a good leader, so upleveling the people around you is part of it. The main difference is the level of accountability, where managers will be more in the weeds of tracking goals, evaluating performance, coordinating with HR, and bringing in new talent.

Setting vision. Okay, some companies do still treat managers as purely people managers, who don't offer critical input on the product. But most leading companies expect managers and ICs to collectively define and push their team towards a north star. The separation of roles is in the how: where managers typically set the framework and ICs fill it in.

Differences:

Process. Improving the environment in which designers do their work is much more uniquely on the management side. While there are plenty of opportunities for ICs to take initiative on this, these tend to be much smaller pieces of the overall pie that managers are held accountable for, which covers team health, review forums, cross-team/org working models, so on.

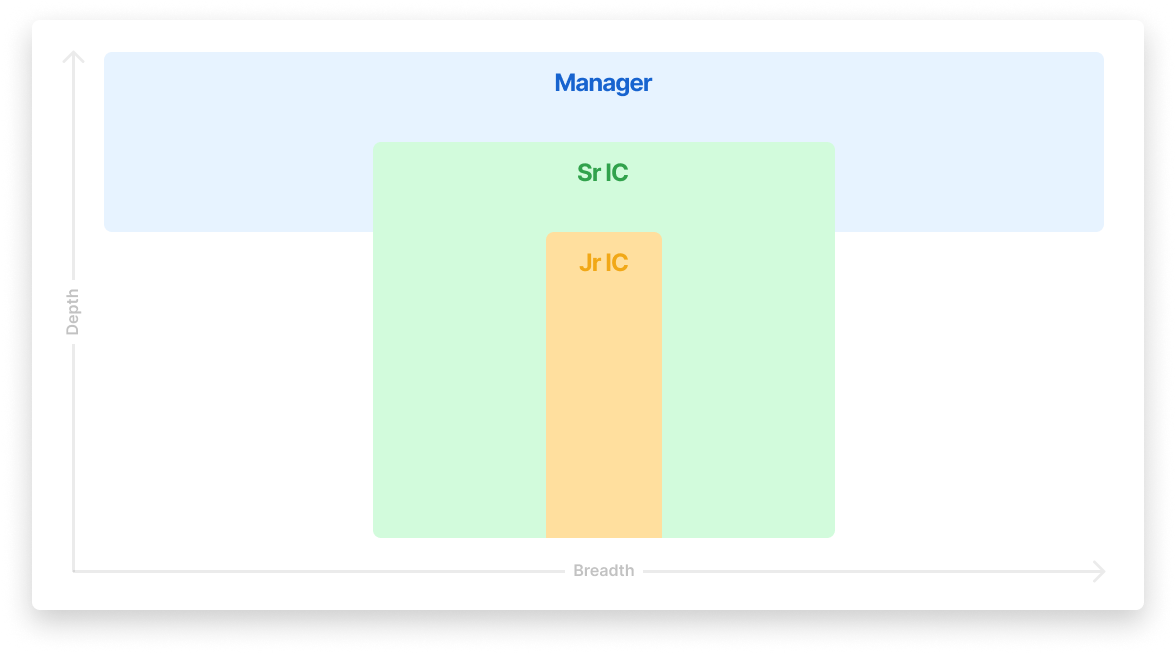

Breadth vs depth. As you grow in any role, so does your scope. However, managers tend to widen and elevate theirselves more compared to senior ICs, who have to remain zoomed in to cover executional details. This means a lot of context switching for managers vs operating at many different levels for senior ICs.

Career predictability. Although the senior IC path is embraced more in recent years, it's still new to the industry, particularly at the Director and VP-level of a large company. You will likely find yourself outnumbered by managing peers than IC peers, which means the higher you go, the less of a frame of reference for where to grow. And because the definition and availability of someone who operates at that seniority varies drastically, mobility between companies becomes a bit trickier. This is due to change though, I'm sure.

Highlights of management

In not being duplicative with incentives I already touched on, I'll be quick here. But brevity != weight of these factors!

Mastery through teaching. I don’t consider myself to have mastered something until I can teach it and management has been a great way to close that final gap. I love public speaking and writing as other outlets but getting direct 1:1 opportunities over a much longer period of time trains this muscle significantly.

Helping your team shine. I'm really not trying to be mushy but when you invest into your team and they come through with their passion and talent, it's like a drug. Or when you can help them hit a milestone or get the promotion they wanted, you feel lucky to have even been there. To keep that high going, you'll want your highest performers to mentor newcomers so your feel-good army grows.

Be awed by your team. While the above is you supporting your team, this is you being supported by them back. Working with senior ICs especially will be a partnership more than anything else. They may very well be better at you in a lot of areas and because of the complimentary nature of your two roles, this makes you feel inspired, not intimidated. The prototypes they spin up breathe life into what used to be a Google Doc and sometimes you just sit back in awe.

Seeing the big picture come together. I've already mentioned higher visibility but with that, comes the privilege of seeing it all come together. Like a painting, you see this team filling in this corner, that team making more vibrant paint, and another team contacting all the galleries to hang it in. It's a beautiful thing to see a massive effort in motion and make progress towards a single goal.

Lowlights of management

While I'm lucky to have found a path that I find personally fulfilling and have a decent amount of success in, I know plenty of people who tried managing and switched back to IC. It isn't for everyone and neither is better than the other. It's about fit and what you want for yourself.

Some common reasons folks struggle with managing:

Underperforming reports. This is by far the most challenging part of management. Managers usually manage because they care about people. But if someone is unmotivated, can't get over their gaps, or is just a bad fit for the role, your relationship with that person may sour and it becomes very emotionally taxing to do right by them and the team.

Fighting for your people. Ah, politics. This is an unfortunate part of any large organization. When people's interests collide or there are few opportunities to share, someone won't get what they want. For instance, if you can't land the raise for a deserving report, it can feel like your fault, even if it was outside of your control.

Being creative. At the end of the day, some people find being in the pixels far more fulfilling and plenty of people regret not ticking that creative box anymore. And on top of that, managers don't get direct credit for a lot of the work they support. As a manager, you have to be okay with passing the spotlight to your reports and gas them up at every opportunity.

Learning to delegate. Especially true for new managers, letting go of control can be hard. Ultimately you have to trust your team to do the job you once did and that it may also take them a little bit to do it well. Your new job is lining up opportunities that fit best with each person's skillset/goals/bandwidth and carving out the best space for them to succeed.

Okay, don't get scared off now. These are challenges, sure, but there are numerous ways to avoid, overcome, or mitigate them. Remind yourself:

Every new challenge is, by definition, uncomfortable. You can’t grow if you stay within your comfort zone and you should look forward to the leader you'll be once you get over the initial hump.

Success truly takes a village. Just because you're a manager doesn’t mean you have to figure out everything alone. Have a support network of senior managers and peers to lean on and take advantage of it as much as possible.

Find your groove. Just because your leadership style may not conform to a stereotype doesn’t mean it’s not valid. If there is value in what you bring to the table, continue to lean into it and be true to yourself.

Advice for incoming managers

Say you've decided management is the right path for you, as you start the transition process, here are some nuggets to send you off with:

Value transparency, not likeability. A huge responsibility of being a manager is carrying sensitive information, whether it is tough feedback or unpleasant news. You may seek to avoid confrontation or sugarcoat the delivery but I guarantee that is short-term gain for long-term detriment. I do a lot to ensure my team trusts me, but that's not the same as liking me. They may like me anyways but prioritizing that over being upfront with them is harmful. This will be a fine art to master and may take a few mistakes to get there.

Express your interest early, not only to prepare yourself to navigate others’ careers but also to set yourself up for the next business opportunity that appears. Unlike being an IC, transitioning and progressing down the management path requires a strong business reason. After all, you can’t be a manager without a team to manage. So being proactive in communicating your interest to your manager, skip, and leadership will go a long way in getting your name in the hat as soon as possible.

Find ways to test out the waters. There are plenty of ways to perform a pseudo-manager role without fully committing. For example, my manager set me up as a mentor to the peers that I would eventually support, making it easier to transition from a dotted reporting line to a solid one. While there were some missing pieces like performance evaluations and coordinating headcount, I exercised other important muscles like goal setting, delivering feedback, and setting priorities for others.

Build strong relationships across your org. One of the most powerful resources your reports have is you as a manager. The leverage and influence you have in your org will therefore impact the amount of visibility you can provide them and how effectively you can unblock them. This means making sure to build solid rapport with their XFN partners, managers across disciplines, and org / product leads.